Get a newsletter every other week from WPA

Join Our Mailing List

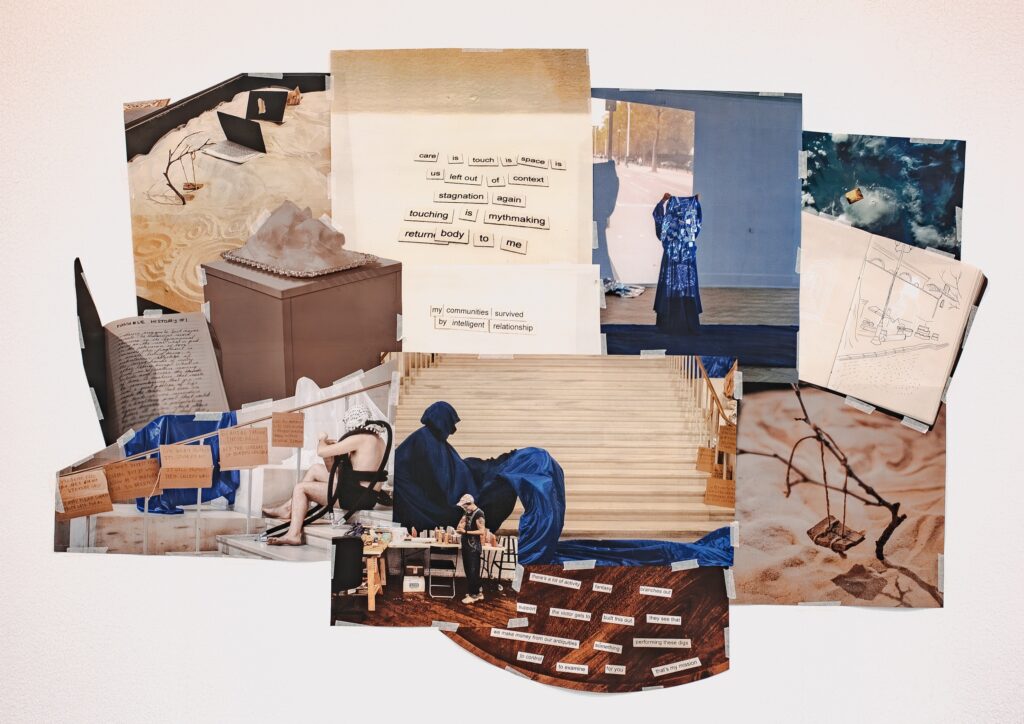

Saj Issa (St. Louis, MO), If I Don’t Take Them, Someone Else Will (2024), glass, 10th c. ceramic shards from Palestine

“Amphoras are an integral part of the landscape along the Mediterranean region. They are nomadic and take form figuratively. I am always so curious about what journey these ancient mobile forms have embarked, whose homes they’ve dwelled in, and the purpose for the end of their life span. It always baffles me witnessing the ways in which Palestinians live with really old things whether it be a family heirloom worn while kneading bread or an ancient Roman pillar that my neighbor uses to prop up their fence. Preciousness is bereft.”

Issa reclaims the fragments she’s collected from the region by pulverizing them and including them as a special ingredient.

Tsedaye Makonnen (Washington, DC), Aberash አበራሽ You Give Light II (2023), wall-mounted sculpture

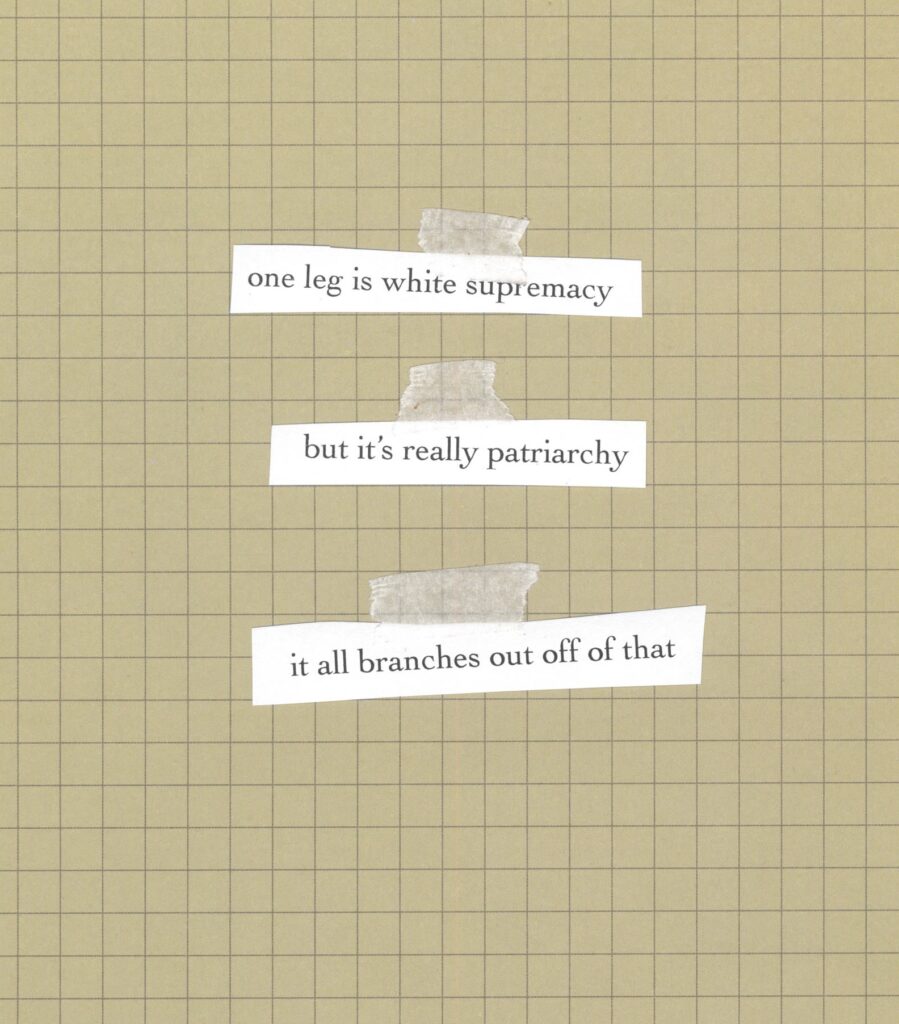

Having engaged in decades of embodied, community-based, and archival research, Makonnen describes mäsqäls as ancient/present/future African universal symbols that are connected to other spiritual codes across the diaspora, with meanings and contexts exceeding their adoption by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Patterned with these indigenous cultural and spiritual symbols, the artist’s stacked light sculptures honor the lives and legacies of Black bodies subjected to transnational forced migration and other ongoing types of state-sanctioned violence and brutality across the globe.

Each lightbox is an obelisk, a totem, and a sanctuary that harbors healing and protective properties. The missing metallic fragments from each pattern are incorporated into Makonnen’s textile works, which are activated through performance.

Jackie Milad (Baltimore, MD), To Be Held and Cared For (2024), acrylic and mixed-media on dyed canvas, epoxy resin clay, acrylic paint and textile collage

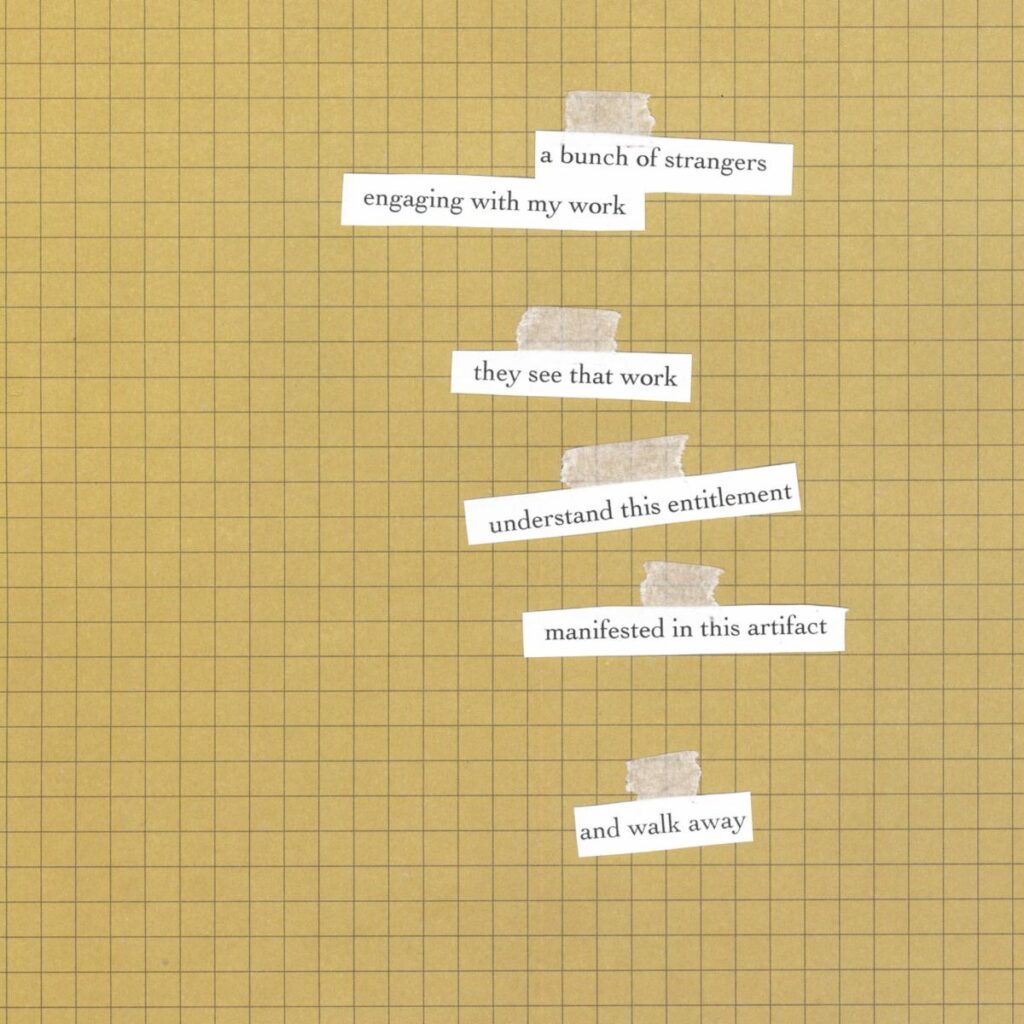

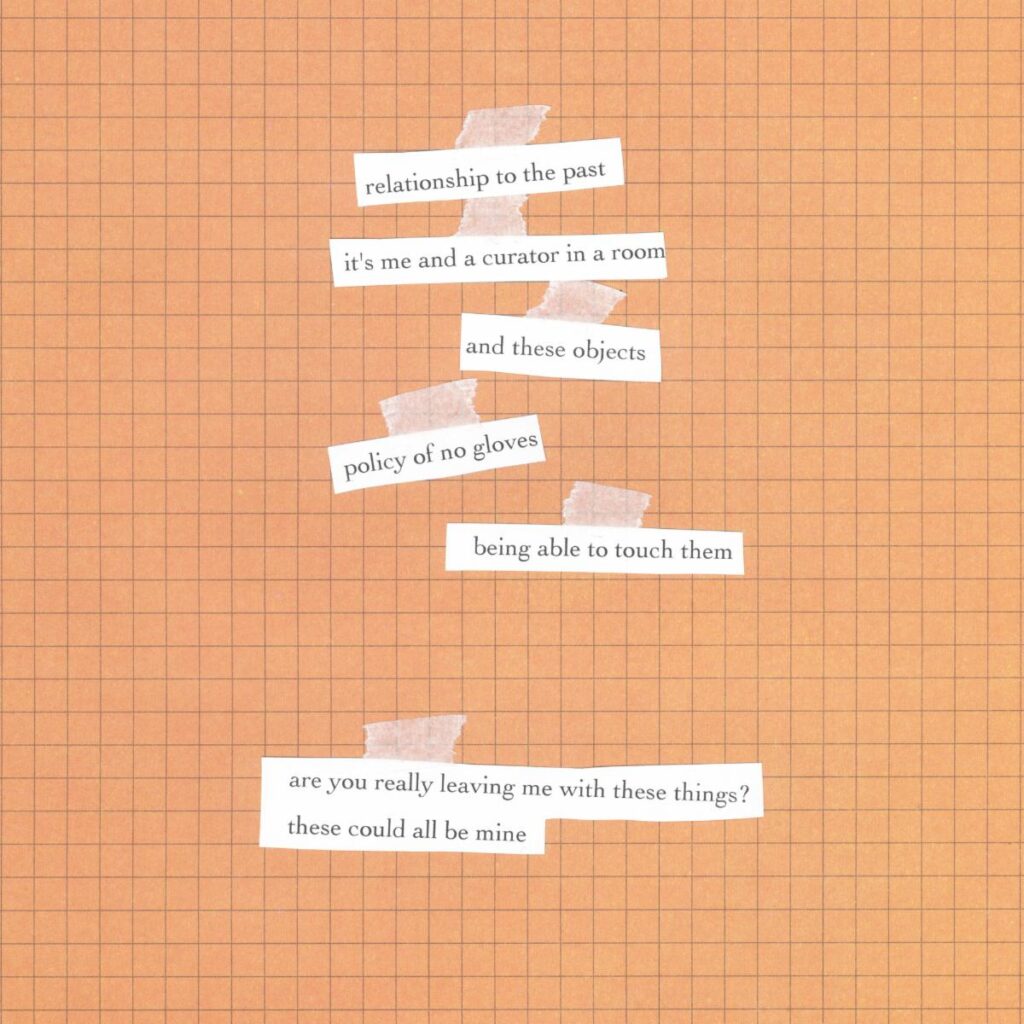

“An object holds history, ancestry, a person’s energy.” Shabti dolls were known as small figurines buried with the dead in ancient Egypt as companions for the afterlife. Nowadays these figures are commodified and fetishized globally, so much so that Egyptologists have no concept of how many are in existence. A great deal of them are being held in institutions with numbers around their necks or on their backs, sometimes stuffed into drawers by the dozen. In recent years, Milad has visited four western institutions in order to commune with these artifacts. Each institution has had its own protocols of care. The artist sits with the figures one by one through the intimate act of drawing, oftentimes in the presence of a curator inside a study room. The collage tapestry layers these drawings with images of her holding the objects, sculptural stand ins as a gesture of them coming to life, together with the artist’s older artworks, and other historical references.

You are invited to step foot on the collage and become a part of it. As you spend time on the piece, you can touch and play with other tactile elements.

Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya (Brooklyn, NY), When The Streets Forget Your Name (2022), Thai cotton, Thai brocade, batik, trim, rice bags, cord, rope, embroidery floss, poly bags, textile scraps, tape, thread, beads

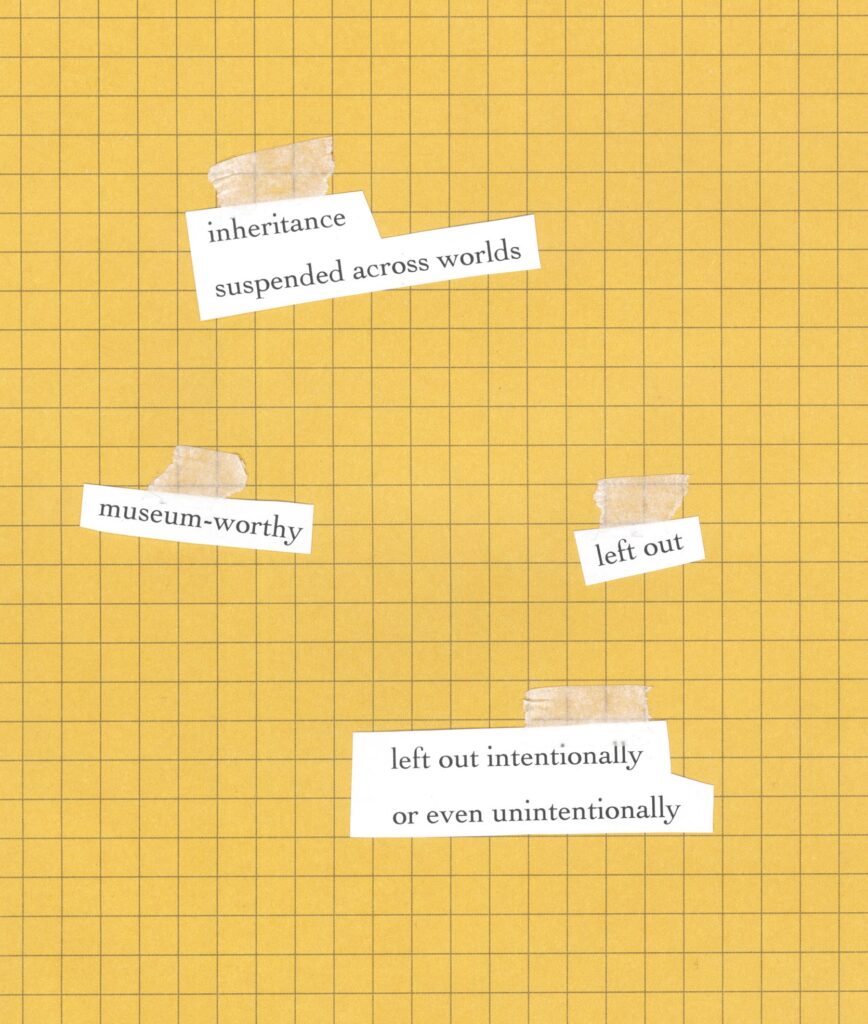

Rice, a staple so ubiquitous it’s often overlooked, parallels the unnoticed work that sustains us. To honor the labor and sacrifices of immigrants embodied in everyday cultural material, Phingbodhipakkiya traveled across the country collecting these rice bags from Asian American mom-and-pop shops. She then wove them together with love, joy, and vibrant color, reclaiming the humble artifacts as symbols of home, identity, and endurance. This tapestry challenges the exclusionary idea that only certain materials, stories, or legacies are worthy of being preserved or inhabiting museum spaces.

In the exhibition, you are invited to engage in the labor of transforming commodified rice, packaged in its familiar bags, by pouring it into a humble threshing basket, a tool still essential to the harvest process.