Get a newsletter every other week from WPA

Join Our Mailing List

Nathalie von Veh: Let’s start with the big picture, what is this project thinking about? What are your intentions and goals?

Mojdeh Rezaeipour: This project is a branch of research informing what Fargo [Nissim Tbakhi] and I have been doing with The Collaborative Fragment Library. In this iteration, I’ve invited different artists, thinkers, scholars, and humans from all around the world to learn about their methodologies to engage with cultural materials in un-museum like ways. The heart of it are the conversations, which have brought forth so many vent-diagrams of themes going through all of our practices and thinking. Something that’s come up a lot lately is the historical use of archeology as a colonial tool—myth-making in service of nation-making. Who gets to write historical context for artifacts? How much of it is completely fabulated? Who do these stories serve? The project has also been a place to process [what it means to] engage with institutions to do this work—institutions to whom our culture, and thereby us, are objects.

Travis Chamberlain: Mojdeh, could you share a little bit about the origins of this project? And where the title comes from?

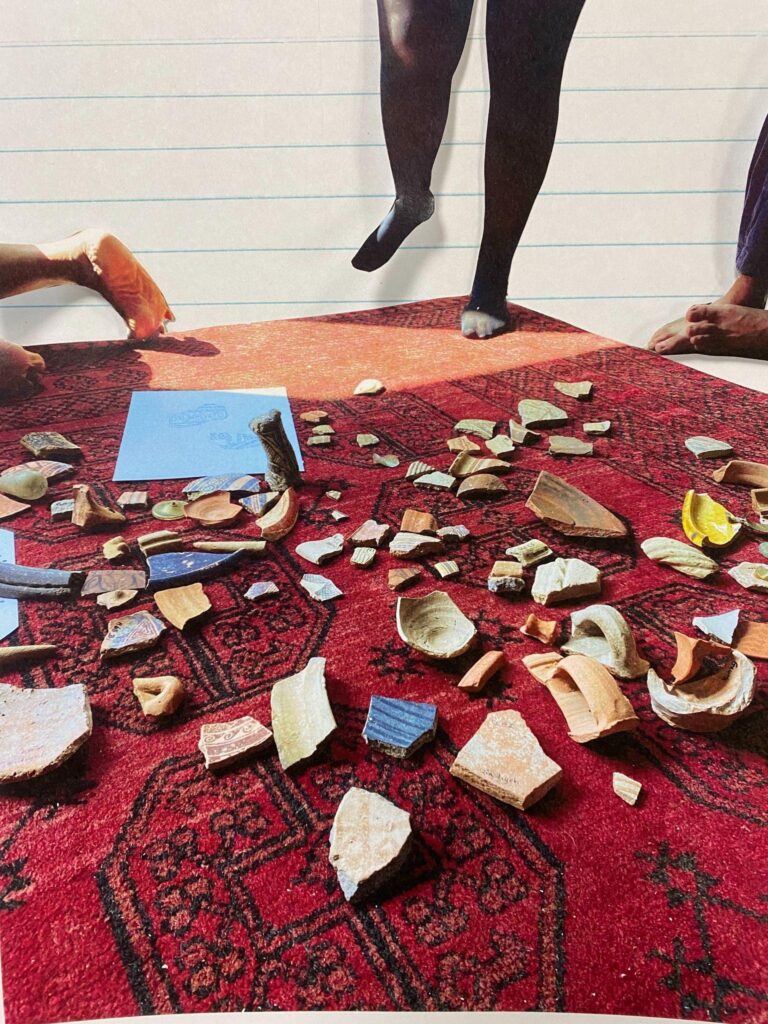

MR: For the past few years, Fargo [Nissim Tbakhi] and I have been imagining together with a collection of 93 ancient pottery fragments excavated across thirty sites throughout the SWANA region encompassing present day Iran, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and in large part occupied Palestine. These fragments initially came to me in 2020 through a process of deaccession via a religious institution that deemed them to have no value. The potsherds were ‘donated’ to the institution—along with many whole vessels now behind vitrines—by a professor of Old Testament who engaged in a decade of biblical archeology across the sites. This sparked a lot of different kinds of ongoing research, but the responsibility of stewarding these objects felt really heavy. My instinct was to let the fragments sit on the floor of my studio for a few weeks and tell me what to do. One of the questions they spoke the loudest was: “Who do we have the potential to bring together?” Led by that, I started to gather a village of people whose lineages lie across these sites with whom to have conversations toward some sort of collective intervention.

In my first conversation with Fargo, he shared with me this book Rubble, which starts out with a powerful anecdote describing how the author [Gaston Gordillo, an Argentinian-Canadian anthropologist] became aware of his own Western and capitalist brainwashedness when it comes to encountering remnants of the past in his research—a tendency to fetishize things for their pastness, an instinct to perfectly preserve them. But arguably making something a cultural heritage site is the fastest way to kill it. At that point I was having a lot of meetings with archeologists and conservators in an effort to learn more about the fragments, and I began to recognize and push back against a similar tendency in myself. Since then Fargo and I—along with dozens of other folks—had more and more imaginative conversations and finally landed on the library model as an alternative structure for the collective interventions. We are starting to test that out now.

Emily Fussner: I liked hearing about how collaborative this process has been from the start. How you recognized that you couldn’t do this on your own when thinking about all these sites. That sense of responsibility. As an artist, what’s the process been like for organizing 93 Fragments with WPA, and what’s that process been like in terms of how you feel like it’s stretched you, or grown your process?

MR: I’m incredibly grateful to WPA as an institution, and as people, for making this project possible. It is truly rare for artists to have this kind of support, financially and otherwise. Once in a while I will, as Jackie [Milad] puts it, have “a bold moment” and reach out to my heroes, and usually they’ll respond! I don’t know why I don’t do it all the time, but it’s really helpful to have someone to write a draft of an email with—thank you, Jordan [Martin, WPA’s Curatorial Production Manager]! Together, it’s easier, you know? The people that I’ve gotten to talk to and learn from and collaborate with so far range from friends who have been my heroes, like Tsedaye [Makonnen] and Fargo, to heroes who I’m now getting the chance to know because of this—people who’ve been pioneers in this way of thinking, these methodologies, for a really long time. When I look at the list of the participants so far, I get giddy honestly. It’s also been incredible to have a partner in Jordan, to be along on the ride for every single conversation so far, to sort out every last detail together, to reflect in an ongoing way on what works and what doesn’t work and being open with me about that in real time. As my visions and thinking have gotten bigger these past couple of years, I’ve been up against a learning curve of working with a larger team inside my sometimes maddening devotion to a process-oriented practice. Jordan recently offered the helpful framing of planning ahead as a practice of care for others, which is really present with me right now as a growing pain.