For our monthly newsletter in November, WPA’s very own Jordan Martin and Travis Chamberlain discussed the ways in which WPA supports artists through frameworks of care and collaboration.

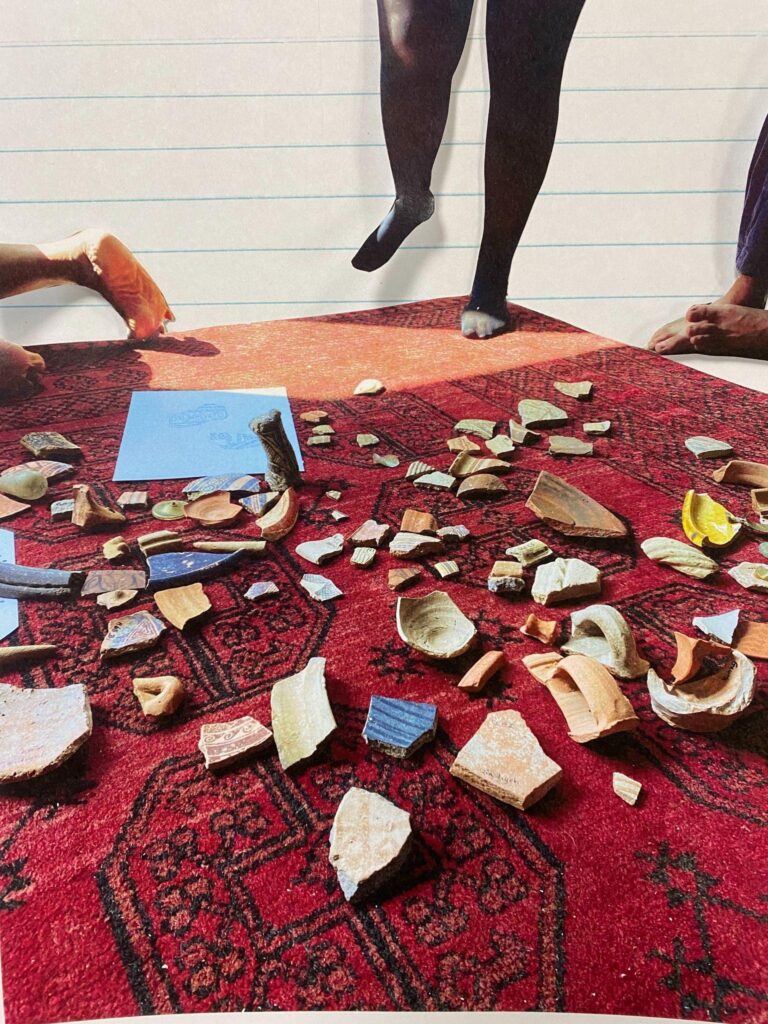

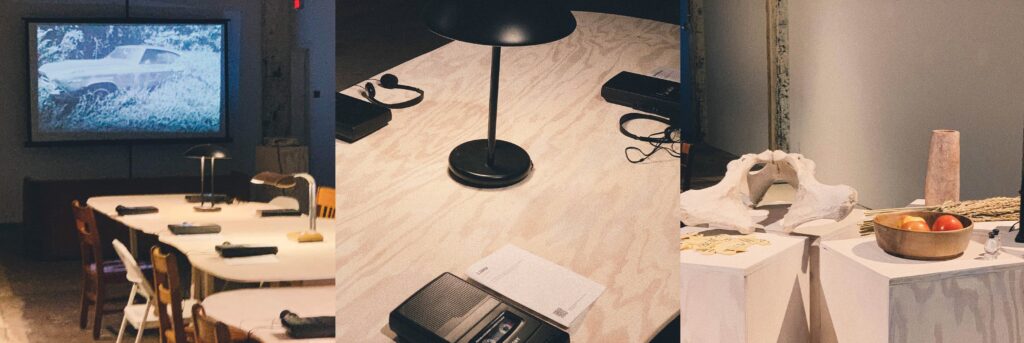

Travis Chamberlain: We’ve just opened this amazing exhibition with Misha Ilin, meta-meta (on view through November 18). Misha’s project has been years in the making, starting in 2021 with a research residency that lasted several months over the winter and included some moments where he was actually living at WPA, performing his research with folks almost exclusively through the internet because this was in the height of COVID.

Could you talk a little bit about how WPA and you specifically, as our Curatorial Production Manager, supported Misha then and throughout the entire process of project development? How have you made sure he’s had the support he’s needed in the midst of a global pandemic and so much ongoing uncertainty?

Jordan Martin: The most significant part is being able to have one-on-one conversations with the artist so I can get really familiar with what they value most and then being a liaison that gets the team aware of those values so that we can all adapt to them. One thing that is a definite strength of ours is that we’re nimble. We’re not this huge 100-person team. It’s just the five of us.

I’m able to distill what’s most important to the artist and then find ways and systems to get us all on board so that we can support whomever we’re working with. With Misha, he really represents the type of artist that we want to continue working with, which is an artist who does not want to work in isolation but wants to connect with like minds or even a stranger on the street. He wants to take his research and connect with the public around him. I think that is a crucial part of the work that we do, so supporting that was already in alignment.

And yeah, it’s about figuring out what the values are of this particular artist, clearing the space, and making systems and processes that feel in alignment with those values each and every project, which is a challenge. But it also keeps things exciting.

TC: How have world circumstances like COVID informed how you go about working with artists to make sure that the values piece is protected and that they’re getting the support they need to move through that moment with us?

JM: That was a wild time. It still is a wild time. But I’d say it’s about adaptability and how nimble you must be during a global pandemic. I don’t have the language to explain the level of skillful flexibility you have to reach as a team, but one thing I try to always center is that we’re working with human beings with really great ideas, and with that, we can find ways to adapt, change, shift and, and figure out the best ways to present these ideas with care and awareness of everyone’s capacity, even more so during a global pandemic.

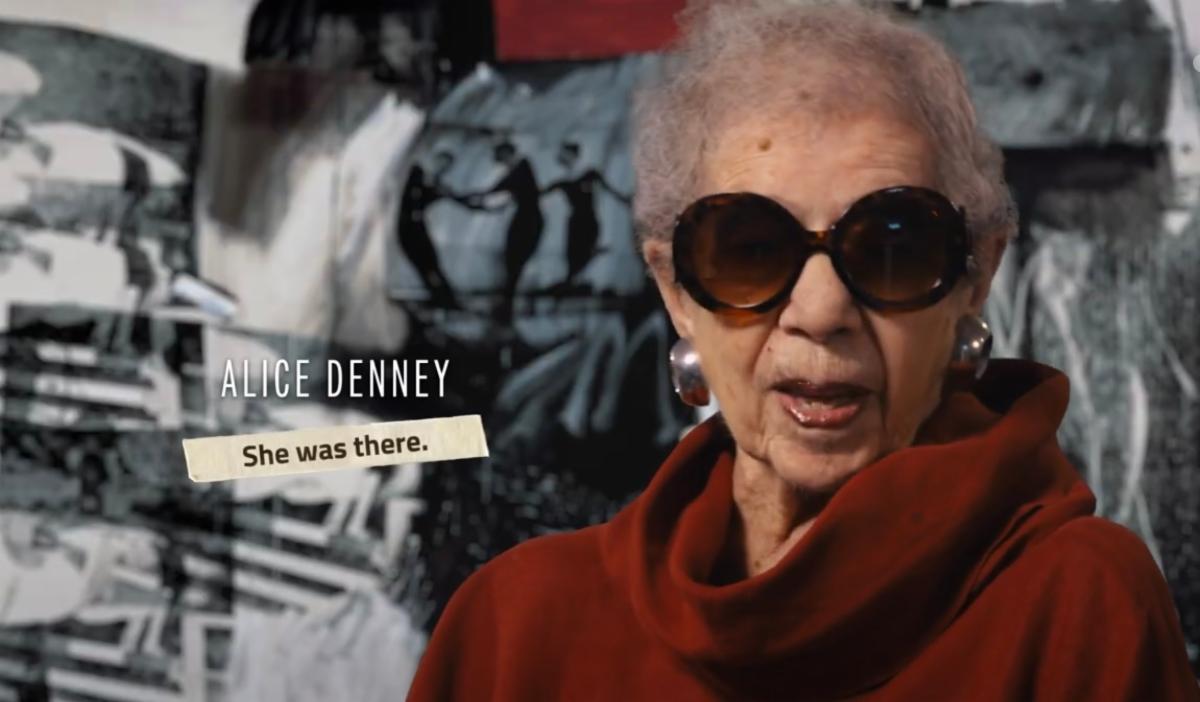

One project I worked on during the height of the pandemic was Black Women as/and the Living Archive. We created this whole project to be in a physical space; there was an installation plan and glorious grand mood boards of how to bring it to life. We had to shift that vision in a matter of weeks when we recognized it was not safe for us to be in the same room.

If you have a strong creative idea or research point of view, you can take those ideas and shift them as need be. Because we cared about the artists, we cared about the attendees. And to be honest, it made the project stronger. We reached collaborators that we wouldn’t have been able to bring to DC, and we reached audiences that were outside of DC.

So with adaptation and trying to stick to the core components of an idea or research inquiry, you can be more flexible and actually have an outcome that’s better than expected. And our unexpected outcome was a book! We created a publication that was not in any of our visions for the project. And it’s a publication that we’re all really proud of, and it has had deep influences on the publication that we just published with Misha (meta-meta: book of instructions) that’s on sale now.

Supporting the creation of artist publications has been a rewarding endeavor as an institution, and I don’t know if we ever would have reached that if it wasn’t for our nimbleness during COVID.

TC: And, it seems in contrast, Misha’s project was conceived within the context of COVID in a much more tangible, real way. It’s interesting now seeing it as an exhibition and a publication, how much–what you were talking about with Black Women as/and the Living Archive—how much that groundwork has really supported what Misha wanted to look into with his work?

I’m wondering with Misha’s project, what has it taught you that is unique, what have you taken from it that has been a unique experience for you? How has it supported your growth as a curatorial caregiver?

JM: Oh wow! That’s my title. I have a title now! Curatorial Production Manager just doesn’t have the vibes I was looking for, but caretaker does!

TC: [laughter] Caregiver—caregiver! You don’t take, you give. We’ll change that on the website ASAP.

JM: I learn so much from every project because I’m working so closely with an individual or sometimes a collective, and it’s really a wonderful experience collaborating and learning how support looks different for every single artist.

One thing that I learn often with every project and Misha’s project also brings this up for me is how harboring control is not necessary.

I can sometimes get stuck in my own conventions of how something should look or how it should work, and working with Misha, and working with any artist, I’m constantly reminded that though it may be helpful for artists to be made aware of these certain conventions, I don’t need to hold on to them. They’re not always the answer; they’re not always the best way to bring an audience into an idea. But it’s necessary to have trust in collaboration, so I challenge myself to remain as open as possible and, and offer those conventions as something to fall back on. It creates space for the team and artists to aspire for something that’s a little bit more challenging or experimental.

Misha has definitely taught me that; all the artists teach me that in different ways. But specifically, Misha has taken performance, research, and instruction-based practices and put them into a publication, so the intended experience of his publication is not just picking up the book and reading it, but you’re actually being invited to perform and think about yourself as a participant and step outside of what you think a conventional publication would look like or work. You have to be open to the whimsical nature of his practice.

TC: How do you work with artists to make sure WPA’s core values of collaboration, inclusivity and experimentation are held and centered in their work with us? How do these values shape their work and what sort of unique outcomes can this produce?

JM: Well, they’re values that I hold personally. That value of collaboration shows up with me. It’s really just about knowing that I bring those values wherever I go and consistently questioning throughout the duration of the project to see if there is tighter alignment or things that we could do to exemplify that more. I think it’s also interesting how different projects tap into those values in different ways and expand our understanding of how those values can be lived and realized through art and the production of art.

TC: My last question is what are you excited for in the month ahead? But also what do you, Jordan, need in the month ahead?

JM: We are a really close-knit team, and prior to your arrival, Travis, we were running this ship of an organization with Alexandra as the interim director and all of us picking up any and every role it took to keep things going. And we are also a very ambitious team. People often think we are this mid-size organization when it’s just us, and I think I can speak for the team when I say, we all need some rest. But individually, I definitely could use rest that looks like reflection, and rest that looks like future casting. In the winter we’ll have some time to do a little bit of future casting and a little bit of dreaming together. And I look forward to that.

As far as what I’m excited about this month, there are two programs as part of meta-meta this month that I’m really excited about. The first is happening tonight (meta-meta: Performance with Josh Coyne, November 2). I can’t think of the last time we had a musical performance at WPA. So I’m really excited to bring that energy to WPA.

And then, having Colby Chamberlain come down from Cleveland and dive into the intellectual headiness of Misha’s project (November 17th) is something that I think we’re all looking forward to before we close things out.

Around the end of the month, it’s more planning to be around family and cooking huge meals which is something I also look forward to. I’m definitely a dinner party girl. I want to have all the dinner party invites.

TC: I have one bonus question. So we have our annual Open Call happening right now, which is a program initiative where we invite DC-area artists to propose projects in a pop-up format.This year, we’ve invited artists to respond to a question: “Where should we start?” The deadline for Open Call proposals is November 14th, which is the same as our deadline for our Wherewithal Regranting program. But I want to ask you, Jordan, where should we start?

JM: [laughing] Oh my goodness!! I would say we could start wherever the people and communities we love most are. I feel like ‘tis the season to connect with your people, spend time and restore each other. We start with those coveted and cherished relationships supporting each other and loving up on each other.

TC: Thank you Jordan. That was fabulous.